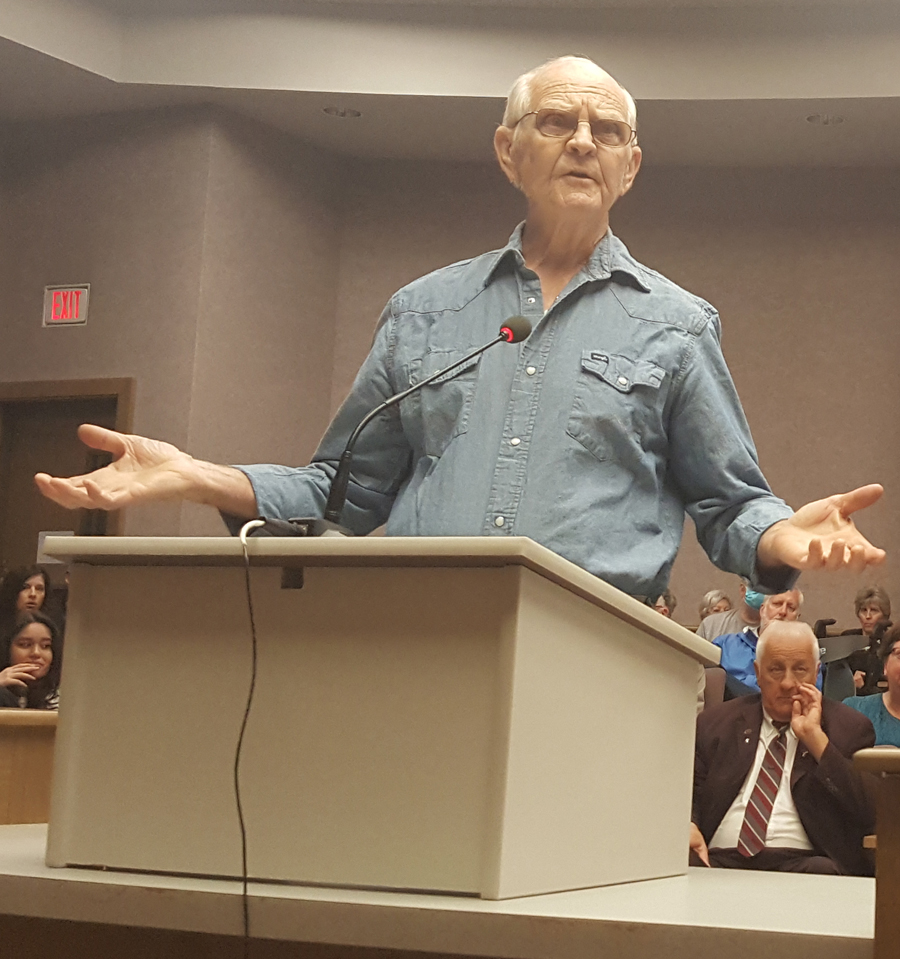

Photo by David Tulis – Chester Green, a longtime resident of South Moore Road, speaks to the East Ridge City Council about the ERHRA boundary map during Thursday’s City Council meeting.

About 150 residents pack city council chambers Thursday in a rare show of civic spirit among a people who usually let elected officials work without supervision.

But more than 16 people rankled at the threat of eminent domain of their houses have words of anger and dismay at a 25-page plan created mysteriously as a sort of legal bulldozer, one that obtains powers in state law to fight “blight” and bring “development” or “redevelopment” to many neglected or sleepy parts of the city of 21,500 people.

City Council members such as Esther Helton and Brian Williams join in expressions of indignation (“We need to go back to the drawing board,” says Mrs. Helton, a candidate for the state house). The authorities’ mood reflects that of residents: Yes, the housing and redevelopment authority has overstepped its powers.

The council — which has final say-so over the authority’s doings — promises it will protect residents and protests that it would never throw residents out of their houses in the interest of commercial development with its high volume of cash flow.

Vice Mayor Larry Sewell, formerly a newspaper circulation official and today a school bus driver, says repeatedly to a string of complainants that the council will order a redo of the map, even though the plan and map have not officially come before that body for presentation. The map shows hundreds of parcels as highlighted rectangles, ones that hotheads among the homeowners might suggest are colored red as if in blood.

‘Virtuous cycle,’ but ‘very distressing’

The plan covers every detail of city life, from boarded-up houses choked with weeds to transportation grants. “The completion of these projects will help the city build from its commercial core to strengthen its adjacent neighborhoods and the physical linkages to them. This will create a virtuous cycle of human activity, financial investment and economic expansion.”

“I didn’t receive a letter,” bellows Brian Graydon, a well-fed chef who works seven days a week for a month at a time and whose yard draws neglect notices from the city.

“But I live right on the edge. So, according to which map I look at, I either lose my backyard, or I lose my house — or I’m fine. And this is very distressing, and very stress causing. I can’t imagine being an older person having gotten this letter.”

“This housing authority was appointed; it is not elected commission,” worries Meredith Moore, 30, who works at a Christian nonprofit. “And it seems like very small and secretive representation of our populace a large. Not only that, it’s an incredible amount of power to give to a body of individuals. I’m also concerned about the fact that they don’t have proper credentials for this kind of massive undertaking. .

The 25-page “East Ridge Development Plan” provides vague language suggesting a impersonal bureaucratic combine that reaches down into neighborhoods like an octopus, suggests resident Francis Pope, strangling home ownership in favor of stores, parking lots, and eatery awnings. Mrs. Pope sees “no rhyme or reason” in the map or the plan, and demands city council investigate how it came to be drafted.

To which council member Brian Williams tells city manager J. Scott Miller that he should tell the housing authority to “substantially reduce” the plan, which he says has no hidden agenda; it should “back up and start slow,” Mr. Williams says.

Do more than that, suggest David Bostain, a BlueCross staffer, and his wife, Lesley, a dental hygienist, both at the microphone. Abolish the board that “blindsided” the citizenry, they tell council members. “It was very disturbing to see that letter” that day he was out doing yard work, Mr. Bostain says. His mailpiece was one of 5,300 items of public notice.

Mayor Brent Lambert is absent because of a stomach bug among his children, according to Vice Mayor Sewell. But residents view his absence as the political calculation of an ambitious politician who wants big government and richer tax cashflow but conveniently ducks away the first night the public can deliver its thunder and lightning.

Dick Cook, editor of EastRidgeNewsOnline.com and a lifelong East Ridge resident, has never seen so much passion and anger among residents. Petty scandals and city hall snafus may pass with little notice, but the citizenry takes a seizure threat on one’s front porch personally.

Seeking Help for Lawsuit

East Ridge resident Jody Grant is not one to partake in mere talk. Knowing that litigation may be the only way to abate official ambition and planner glee, she contacted Institute for Justice in Arlington, Va. That public interest law firm is litigating 43 cases in 26 states, a group whose activism has defeated 64 eminent domain projects and blight designations.

“People who are deciding the fate of the city have not read the 25-page document,” Miss Grant says, “and were not able to answer citizens’ questions in regard to development plans.” She emailed the plan to Robert McNamara, chief counsel for the institute, and he “responded very quickly and said we have a potential for eminent domain.”

The institute offers litigation to challenge lawless government — but also guidance on community activism. “We’re unable to litigate or become actively involved in every situation,” the group says, “we will provide you with the tools and tips you need to effectively fight the abuse of government power in your own backyard. We will do whatever we can to help you defend your right to earn an honest living free from arbitrary regulations, choose the school that is right for your child, keep the private property you rightfully own, and protect your right to speak freely.”

City government is operating its authority under the Tenn. Code Ann. § 13-20-201 and provisions following. Blight is granted a social and moral character; cities fight it by proxy, through housing authorities.

“‘Blighted areas’ are areas, including slum areas, with buildings or improvements that, by reason of dilapidation, obsolescence, overcrowding, lack of ventilation, light and sanitary facilities, deleterious land use, or any combination of these or other factors, are detrimental to the safety, health, morals, or welfare of the community. ‘Welfare of the community’ does not include solely a loss of property value to surrounding properties, nor does it include the need for increased tax revenues.”

David Tulis hosts a show 9-11 a.m. weekdays on NoogaRadio 92.7 FM and 95.3 FM HD4, covering local economy in Hamilton County and beyond.